| In March 1942 I was assigned to "F" Flight, Ferry

Command in Harwell, and on 1 April I flew to St Eval, at the western tip

of England. Our mission was to ferry airplanes from England to Egypt. At

6.25 a.m. on 2 April we left St Eval for Gibraltar in a Wellington Bomber,

flying for 9 hours over the sea, along the northern tip of Spain and along

the coast of Portugal. I do not remember if we saw land before we reached

our destination. A bomber crew usually consisted of the captain, a navigator,

two wireless operators, and two gunners. On this crew our captain was Flying

Officer Penman, a New Zealander, the wireless operator was Ken Buckley

from Bolton, England, near Manchester, and I was the navigator. Unfortunately

I don't remember the names of the others. Ken and I remained friends and

corresponded regularly until his death in the early 1980s. This was my

first major trip as a navigator. Looking back I realize how inexperienced

we all were, but no one gave it a thought, probably a good thing under

the circumstances.

Three days later, on 5 April, we left Gibraltar at l.05 p.m. for Malta.

To avoid detection we flew low over the Mediterranean Sea for some time.

The Germans occupied Sicily and were sending, by wireless, exactly the

same navigational signal the British were sending from Malta. It was up

to the navigator not to be fooled by this German signal, since it could

lead you to Sicily. There were rumours that some had been fooled and were

captured. I did not rely on any wireless bearing for my navigation but

did some double checking once or twice. The flight took 8 hours, 15 minutes,

and it was already dark when we arrived in Malta, where a blackout was

in effect. Because the island of Malta is so small, it can be seen in its

entirety from the air and as a navigator it was reassuring to realize that

we were definitely over Malta and not over Sicily.

The island of Malta was under very heavy bombardment by the Germans;

it went on nearly 24 hours a day. Orders were that on hearing the air sirens,

we, the Allied military personnel, were not to rush and be the first ones

to take cover in the bomb shelters, this to show courage and also not to

sow panic amongst the Maltese. The island of Malta was awarded the George

Cross by King George VI in recognition of the bravery, suffering, and the

outstanding determination and steadfastness of its people, who, against

all odds, never gave up.

The RAF's plan was that on landing at Malta the airplane would be refuelled,

another crew would take it over, and it would continue on to Egypt, where

General Montgomery was amassing all the equipment possible for a major

offensive against the German's General Rommel. This battle eventually took

place at El Alamein, Egypt, and was won by the Allies. It was a decisive

victory and the turning point of the war in the Middle East.

The plan that a new crew would take over the aircraft in Malta was sound

in theory, but in practice not very successful. Airplanes got bombed on

the airstrips and experienced many mechanical problems, creating an accumulation

of air crews waiting for their turn to move on. As a result, we were in

Malta for 7 days.

Our crew's turn to leave came on 11 April 1942, but to our bitter disappointment

we experienced engine problems and could not take off. The Maltese people

were not asked to leave the island, but if transportation was available

these unfortunate people could take advantage of it. On our first attempt

to leave four or five Maltese boarded our plane. It was very sad to see

the expression of despair on their faces when the flight was cancelled,

but all we could do was sympathize with them and wish them better luck

on their next try. Since the Wellington was not suited for passengers,

we would have been overcrowded and I wondered how I would navigate under

such conditions.

Our crew's second chance came on the following evening, 12 April 1942,

and, surprisingly, we did not have extra passengers. The instructions were:

"Once airborne there is no turning back. Get to Egypt the best way

you can." Soon after take-off we experienced engine trouble and had

difficulty maintaining our altitude. We had left Malta at 2 a.m. and at

daybreak we were over Egypt. We were confident we were in Allied territory,

since we had not seen any ground fighting. We were losing altitude constantly,

so our captain, Pilot Officer Penman, elected to make a "wheels up"

or "belly landing" in the Sahara. Unknowingly, yet quite luckily,

we had flown over a British soldier on motorcycle patrol. He realized we

were in trouble, having watched us disappear behind the sand dunes and

having seen the cloud of dust. Because the Wellington was of geodesic construction

it helped us make a safe but shaky landing. Everyone got out quickly, rubbed

the sand from their eyes, and checked on each other. Fortunately, no one

was injured. At the same time, the soldier on patrol arrived on the scene,

followed by ambulances and army trucks. We were taken to an army camp located

some distance from actual military operations, where we were well cared

for by the British Army.

While we were with the army waiting for the RAF to pick us up, we saw

how the natives operated in and around the camp. At night there was considerable

pilfering, supposedly by these natives. Everything imaginable would disappear.

The British Army guards on duty were never able to apprehend even one thief,

being outwitted at each attempt. In desperation the Army replaced their

guards, in the middle of the night, with Gurkas, warriors from Nepal, India,

serving with the British in the war. They were famous for their stealth

and for executing orders to the limit. Their policy was "kill first

and ask questions later." Needless to say, the pilfering ceased. The

Gurkas would have been my choice for a personal bodyguard. Incidentally,

we were given orders to carry a lantern when going from one tent to the

other, which we never forgot.

The British Army had notified the RAF in Cairo, but it was 8 or 9 days

before we were picked up and able to report to the proper authorities there.

After the debriefing and filing of reports were completed, we were ready

to meet our friends who had made it safely to Cairo ahead of us. We were

told to go to the New Zealand Club and that "the RAF boys would be

there." When we walked into the club those who knew us were astounded.

Orange juice was passed around (liquor was not sold there). It was an RAF

policy that whenever a plane did not reach its destination, it was considered

a total loss and no effort was made to locate it. In other words, "you

were written off," and so we had been "written off." Jack

Portch, with whom I had trained at OTU in Moreton-in-Marsh, was flying

the same missions as I. When I met him at the New Zealand Club he told

me that my aircraft had been reported missing. Together we went to the

telegraph office in Cairo and I cabled the following message to my mother,

"Disregard any news you may have received. I am well and safe in Egypt."

All letters and telegrams were sent to my mother, since my father was away

from home for several months at a time, fishing aboard American schooners

out of Gloucester, Mass. My mother never received the message. The telegram

to my mother announcing that I was missing had come from the Department

of National Defence in Ottawa and it read "We regret to inform you

that your son Sgt. A. S. Bourque has been reported missing as a result

of air operations over Egypt." This message was received on a Thursday

and exactly one week later a second message was received from the RCAF

in England with the news that I was safe. There were no details and this

apparently caused much confusion at home. However, the mere fact that I

was safe was very welcome. At my parish church, prayers were requested

for my safety. I was, as it is said in French, "recommendé

aux prières." I was told that when my mother received the message

that I was missing, she was silent, despite her feelings, but on receiving

the message that I was "safe" she was emotionally overcome.

To celebrate our safe arrival in Cairo the "boys" decided

to take us out, supposedly to the best nightclub in town. The nightclub

appeared to be respectable and the show was a "belly dancer"

who performed on a stage in the centre of the floor. A comical but drunken

sailor decided to join her on the stage and everything went smoothly until

a soldier decided that he also would be part of the show. Some shoving

took place and suddenly the entire place erupted, bottles were thrown around,

mirrors were smashed, and fights broke out everywhere. We managed to make

a quick and safe getaway. Needless to say, we never went back. Traditionally

there has always been rivalry between the British army, navy, and air force

and at times the arguments would turn into fist fights. This was the only

one I ever witnessed, however.

|

Although Arab is Egypt's official language, French and

English are also spoken. One day while shopping with an English-speaking

friend, I overheard the clerks discussing in French how much they would

increase the price of anything we bought. On realizing that I had understood

the conversation they refused to serve us.

In the parks in Cairo, we would buy from the paperboys a local English

newspaper for, say three cents. We finished reading it very quickly and

if the newspaper was left on the bench the paperboys would retrieve it

and resell it for another three cents. Of course, the game was that we

would try to sell it back to them for one or more cents.

While in Egypt, I visited the Pyramids. I went inside one and climbed

up a second one. A guide holding a candle led you inside, the ceilings

were very low, it was hot and humid, and the smell was foul, not altogether

a pleasant experience. Furthermore I was not necessarily interested in

history at that time. During our stay in Cairo my pilot, Pilot Officer

Penman became ill with pneumonia and I never saw him again. It was probably

in the 1970s that Ken Buckley told me that Penman had survived the war

and had returned to his native New Zealand.

My next adventure began with orders for us to travel to Lagos, Nigeria,

on the west coast of Africa, where we were to board a ship bound for England.

Eventually we would ferry another plane from England to Egypt. On 16 May

1942 we left as passengers on board a civilian Pan-American Airways DC3

and flew to Khartoum, Sudan, in 6 hours, 20 minutes. We stayed there overnight

and the next day we flew across Northern Africa to Kano, in the northern

part of Nigeria, in 10 hours, 35 minutes. After another overnight stay,

we flew on to Lagos, in 2 hours, 50 minutes. There we were billeted in

a camp outside the city limits, which like most of the camps in West Africa,

the Middle East, and later in India, were lacking many of the comforts

of life. We gradually learned to make the best of what was available. This

trip to Lagos was the last one on which Ken Buckley and I were together.

Ken stayed with Ferry Command for the duration of the war. On one occasion

he came to India, but we didn't meet.

The official language in Nigeria is English, but several other languages

are also widely spoken. My batman, commonly called a "boy" or

"bearer," spoke English. He accompanied me whenever I went to

the city and generally protected me from being victimized by vendors and

merchants. Lagos was a port of call for convoys sailing to and from England

to South Africa and beyond. Several weeks passed and our ship still had

not arrived. We had nothing to do, social life was non-existent, and the

weather was hot. Nigeria is just five degrees above the equator.

Then, one day, a crew of 8, with Sergeant Cecil Cox as pilot and myself

as navigator, was chosen to fly as civilian passengers to England, again

supposedly on an urgent mission to ferry another plane to Egypt. Our flight

plan included several stopovers, two of which were in neutral countries,

namely Lisbon in Portugal and Shannon Airport in Ireland. We were issued

false passports (refer to Passport Nigeria No. 35212). I was supposedly

a civil servant. I wore a white open-necked shirt and grey flannel trousers,

while travelling incognito.

We took off from Lagos on 14 July 1942 on an Empire Sutherland Flying

Boat and flew for 13 hours to Bathurst. The city of Bathurst, now called

Banjul, is in Gambia, a small British colony on the west coast of Africa.

There we had to change aircraft. Five days later, when we finally left

on a Boeing Clipper, we were joined by 12 or 13 other passengers, one of

whom we suspected was a brigadier. Since we were travelling incognito,

we were simply "Mr" to everyone. No one revealed their true identity.

Rumours were that this Boeing Clipper had just returned from flying Prime

Minister Churchill to Washington. Flying in a plane that had transported

Prime Minister Churchill made us think we were rather important. We left

on 19 July and 14 hours, 30 minutes later we arrived in Lisbon, Portugal.

Our stop in Lisbon was to be very brief, but, due to bad weather in Ireland,

the flight couldn't carry on and as a result we stayed in Lisbon for two

days. Our military kit bags were supposedly well hidden in the plane's

baggage compartment, but somehow they were all brought out in front of

the custom and immigration officers, who turned a blind eye to all the

commotion. In reality, we should have been interned. Obviously Portugal

was leaning in favour of the Allies. Our group was taken to the British

consul, who certainly knew who we were. He took us for lunch and we stayed

at a hotel in Estoril, the beach resort area. We were warned not to talk

to anyone and not to fraternize with any strangers. We actually spent some

time on the beach, but no one ever approached us.

When we left Lisbon on 21 July, the weather was still bad in Ireland,

so we flew directly to Poole, England, close to Bournemouth on a flight

which lasted 8 hours, 30 minutes. There we put on our military uniforms

and proceeded to the Air Ministry in London. On arrival at the office of

the Air Ministry our so-called importance and ego were abruptly shattered

since no one knew who we were. They had never heard of us and were not

impressed with our story. Suddenly, we were just ordinary airmen. We were

told to keep our whereabouts known to the RAF and postings would follow

soon. In the meantime, we were granted leave which I spent in London. I

exchanged telegrams with my parents and found out that my sisters Anna

and Rosalind had both married since I had heard from home about four months

earlier.

While on leave I decided to locate Jean Pierre Bourque - a neighbour

from Sluice Point who was with the West Nova Scotia Regiment. After many

inquiries I received a few discreet hints. Information on the location

of troops in war-time England was not easily obtained. I finally found

the regiment on the south coast of England. We had a pleasant reunion and

I recall we sent a telegram to Jean Pierre's mother telling her of our

get-together. Finding overnight lodging in the area was not easy, for two

reasons. First, rooms were scarce, and secondly, the reputation of the

Canadians for boozing and partying didn't help. I managed to find a suitable

place and before I left the landlady apologized for having at first refused

to rent me a room.

The next posting, in August 1942, was to 1653 Conversion Unit located

at Burn, Yorkshire, just outside the village of Selby and near the city

of York. There we retrained for Consolidated B24 Liberators, which were

four-engine American bombers. They had a wing span of 110 feet, they were

67 feet, 2 inches in length, 18 feet high, and could carry a bomb-load

of 8,000 pounds. Eventually, as we became familiar with the Liberator and

our training was completed, new crews were formed and Cecil Cox and I were

together again. I was the only Canadian on my crew.

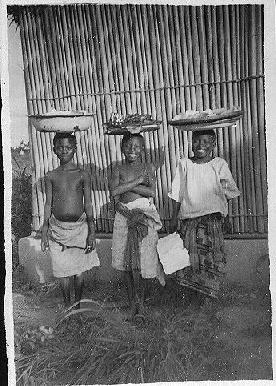

Girls selling peanuts,

Lagos, Nigeria, May 1942.

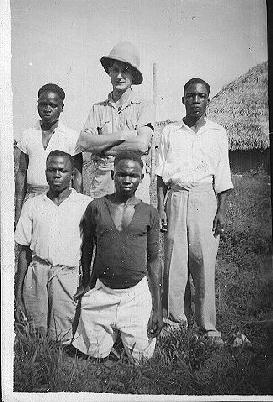

OJI OTIWA, my "bearer", on my

left,

Lagos, Nigeria, May, 1942.

|