|

On arrival in Halifax on 19 November 1940 I was sworn into the RCAF.

My number was R76221. Normally, I would have been posted to the Manning

Depot in Toronto, but because of an epidemic of measles there, I was sent

to the Manning Depot in Brandon, Manitoba. The pay was $1.10 per day. I

left Halifax by train for Brandon on the CNR route, via New Brunswick,

Rivière-du-Loup, and Montreal. I was with a group of recruits who

seemed much older than me and I was somewhat shocked at the beer-drinking

and the general rowdiness which took place. I have no specific recollection

of passing through Quebec City, Montreal, or other places along the way.

At the Manning Depot in Brandon I went through basic training, which

consisted of drills, lectures, and outfitting. Not being familiar with

military ranks, I was at first impressed by the authority seemingly held

by the corporal in charge of the raw recruits like myself. He acted as

if he was the "big boss." We soon got to know what a corporal's

status and functions were. I spent Christmas of 1940 with Peter and Florence

Dibblee in Winnipeg. Florence was from Sluice Point. It was a very enjoyable

break. I don't recall ever being in Winnipeg after that.

Early in 1941 I was posted to Rivers, Manitoba, for guard duty at the

Advanced Navigation School. It was bitterly cold and the job was not very

interesting, marching around the camp boundaries carrying a gun on your

shoulder at all hours of the day and night. How effective I would have

been had I met "the enemy" is questionable.

|

On 4 August 1941 I went back to Rivers, Manitoba, now as a student

at the Advanced Air Navigation School. I learned to navigate by the stars

(astro navigation) and again I flew in Avro Anson airplanes. Although there

are literally millions of stars in the sky, only a very limited number

in each hemisphere can be relied upon for navigational purposes. In order

to establish your position on a navigational map you had to obtain readings

on two stars with a bubble sextant from the airplane's plexiglass astrodome.

(The sextant we used had a bubble as an artificial horizon to obtain the

altitude of the stars, in contrast to a naval sextant which uses the true

horizon.) Then, you plotted these readings on the map and, if your work

had been done accurately, you would obtain your exact position. All this

work involved navigation books, Greenwich time, correct readings, and a

lot of self confidence.

I was fascinated by astro navigation and, with hard work and perseverance,

I managed to pass this course. Graduation Day was on 1 September 1941.

The ceremony was open to the public and largely attended. Among the graduates

was Warren Wortley, originally from Toronto and now living in Comox, British

Columbia. I have always kept in touch with Warren.

My training in Canada was complete and I left Rivers for home, on a

short leave before the next posting, which for myself and the majority

of my colleagues from the course in Rivers was overseas. My two weeks'

leave at home was spent visiting family and friends and bidding everyone

farewell. My brother, Antoine, was to be married on 23 September, but since

I had to report to Halifax a few days before that, I missed the wedding.

|

|

No3 Air Observer's School, Regina, Sask.

Warren Wortey, back row, far right

|

|

Guard duty didn't last long and my next posting was to No. 3 Air Observer

School in Regina, Saskatchewan. This school, along with many others across

Canada, was part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, formed

and operated by Canada and one of this country's major contributions to

the war effort. I was chosen to be an air observer on the assumption that

as a bank employee I was good at mathematics. At the time I was in training,

an air observer was both the navigator and the bomb-aimer of the crew.

Later on, the tasks were divided and performed by two different persons,

a navigator and a bomb-aimer. I found the course very difficult, no doubt

because of my weak educational background. I worked very hard and passed

with 65% (the passing grade was 60%), which was better than some who had

college degrees but failed the exam. I was promoted sergeant air observer

on 23 June 1941. On this course we were flying Avro Ansons, which were

twin-engine airplanes. It was my first experience in an airplane and I

thoroughly enjoyed it. Our pilots were all civilians who, to overcome the

monotony of repeatedly flying the same routes month after month with student

navigators, would occasionally engage in low flying over railway tracks,

etc. They had to be very careful, since they were breaking the rules and

could have been severely reprimanded had they been found out. For the students,

however, it was great fun.

After graduating as an observer I had some time off and with a few

friends went by train to Banff and Lake Louise. I still have snapshots,

taken at that time, of the Great Divide and of some of us riding horseback.

|

On arrival in Halifax five or six of us were told that our names were

being added to the embarkation list for that day and that we would leave

immediately. Hurriedly, we got our inoculations and our baggage was sent

to the ship. Then, we were suddenly taken off the list because somebody

more important than us had priority. We were instructed to go to the ship

and retrieve our baggage, which we did, but getting off the ship was a

major problem. Imagine trying to go down the gangplank carrying your baggage,

on a ship that is about to sail for overseas. Our story was not too plausible,

but eventually an officer came to our rescue and we returned to the depot.

Two days later, on 22 September 1941, my 21st birthday, I sailed for England.

I can't recall the name of the ship. It was small, not overcrowded and

quite comfortable. We joined a convoy and had an uneventful trip.

We landed at Larne, Northern Ireland, took a ferry to Stranraer, Scotland,

and travelled by train to Bournemouth, England. Bournemouth is located

on the English Channel. It was and still is today a resort town with many

hotels, which during the war years were taken over by the Royal Air Force

to billet the airmen from the "colonies," pending postings to

air bases. On the way to Bournemouth the train stopped in the middle of

the night, somewhere in Yorkshire I think, and I could hear the local residents

talking on the station platform. Not being used to their accent I understood

very little and actually questioned whether they were speaking English.

|

|

Advanced Air Navigation School, Rivers, Manitoba,

August, 1941.

|

The next posting was to No. 2 Bombing and Gunnery School

in Mossbank, Saskatchewan. I was there from 23 June to 4 August 1941. The

airplanes we flew there were single-engine Fairy Battles. They were very

noisy and uncomfortable. I really did not enjoy the course, but no doubt

it was all part of the training to become air crew.

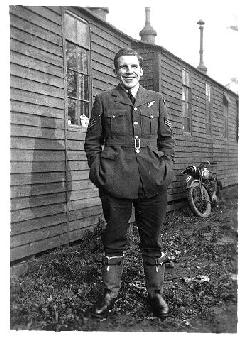

Jack Portch, Moreton-in March, England,

November, 1941.

|

At that time the RCAF did not have its own squadrons, so we Canadians

were assigned to the RAF. They treated us as their own and posted us wherever

we were needed. Eventually the RCAF formed its own squadrons, wings, etc.

and was in full command of its airmen. There was even a French Canadian

squadron, L'Alouette Squadron, No. 425, but as fate would have it I remained

with the RAF throughout the war.

Later in the autumn of 1941 I was posted to No. 21 Operational Training

Unit (O.T.U.) in Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire. This village is in

the Cotswold district, a short distance northwest of Oxford and also near

Banbury (of the nursery rhyme "Banbury Buns"). The airplanes

there were Avro Ansons and Wellington Bombers (2 engines). At this base

crews were formed and we trained for the "real operations." The

term "operations" meant engaging in battle with the enemy and

was commonly referred to as "ops." A tour consisted of so many

"ops."

That year I had Christmas dinner at the Manor House Hotel in Moreton-in-Marsh,

a typical hotel in a small village. I still have in my possession a menu

from this dinner which is signed on the back by Jack Portch, Warren Wortley,

Vern S. Irwin (killed in action in Egypt in October 1942), and by Sandra

and Doris who must have been waitresses, since it was strictly a stag dinner.

Throughout the years I have managed to visit Jack on a regular basis. Unfortunately,

I don't see Warren as often. Destiny has us living far from one another.

|